The

American Revolution

The

Boston Tea Party

(Dec.

16, 1773)

The Boston Tea Party was an act of

political and economic protest against the authority of

the far-away British government to impose taxes upon

American colonies that had no representation in Britain's

Parliament. The English subjects who lived in the

American colonies felt that they should have the same

political rights as other free-born Englishmen; in

particular, the right to have representatives sit in

Parliament and take part in the debates and creation of

laws that affected the colonies.

Following Britain's victory over

France in the French and Indian War, the British

government looked for ways to pay for the debts incurred

by the war. Since the war had largely been fought to

protect the English colonies in America, the government

felt it would be appropriate to let the American

colonists pay for their own defense through the

imposition of new taxes.

The Stamp Act and the Townsend Acts

had imposed multiple taxes on the American colonies as a

way to pay for British administration and defense of the

colonies. These taxes caused considerable political

agitation in America, leading to many protests. The most

violent protest culminated in the infamous Boston

Massacre of 1770, and the most celebrated act of

non-violent protest occurred three years later in what

came to be called the Boston Tea Party.

The British government repealed most

of the onerous tax laws that the Americans complained

about, but kept a tax on tea, which was a part of nearly

everyone's daily meals. The governement wanted to keep

the this tax in place largely to maintain its power to

levy taxes on the colonies. The American colonists

responded by refusing to let the tea ships of the East

India Company (which held the monopoly on shipping tea to

the colonies) dock and unload their taxable cargoes. Tea

ships bound for New York, Philadelphia, and Charleston

were all turned away. The tea ships bound for Boston

managed to dock, but were unable to unload their tea.

Thus, they sat at dock and waited.

When the East India Ship the

Dartmouth arrived in the Boston Harbor in late

November of 1773, Samuel Adams organized a meeting to be

held at Faneuil Hall on November 29. Several thousand

people arrived, forcing the meeting to be re-located to

the larger Old South Meeting House. Adams' meeting passed

a resolution, introduced by Adams, urging the captain of

the Dartmouth to leave Boston Harbor without paying the

import duty. Meanwhile, the meeting chose twenty-five men

to watch over the Dartmouth and ensure that the

tea was not unloaded.

Massachusetts Governor Hutchinson

refused to grant permission for the Dartmouth to

leave without paying the tax. Two more tea ships, the

Eleanor and the Beaver, arrived in Boston

Harbor On December 16, about 7,000 people had again

gathered at the Old South Meeting House. Upon hearing a

report that Governor Hutchinson still refused to let the

tea ships leave, Samuel Adams announced that "This

meeting can do nothing further to save the country."

According to eyewitness accounts, people did not leave

the meeting until ten or fifteen minutes after Adams's

alleged "signal," and Adams in fact tried to stop people

from leaving because the meeting was not yet

over.

While Samuel Adams tried to reassert

control of the meeting, quite a few Bostonians left the

Old South Meeting House and headed toward Boston Harbor.

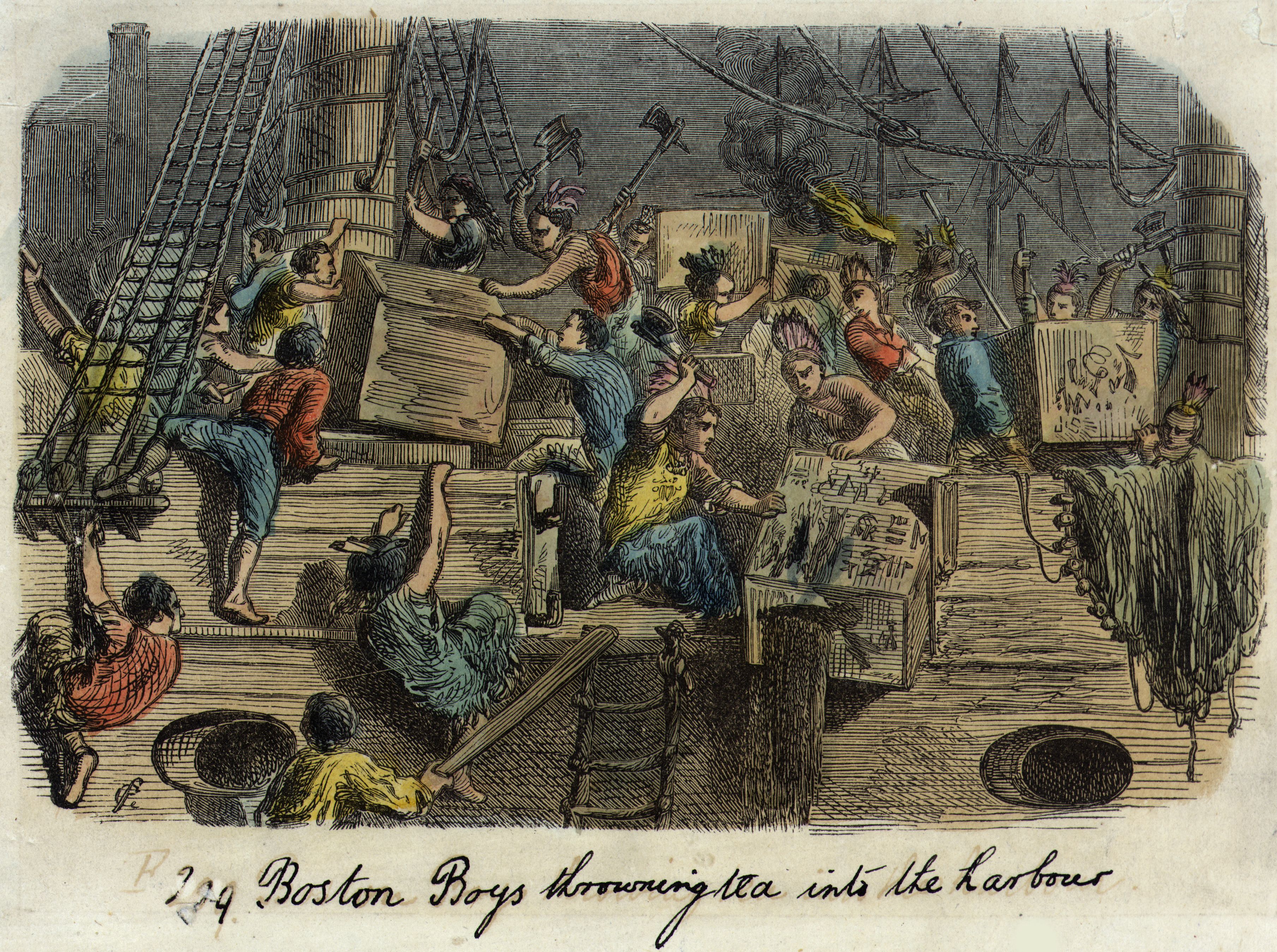

Later that evening, a group of 30 to 130 men, some of

them dressed as Mohawk Indians, forced their way onto the

three tea ships, and, over the next three hours, dumped

all 342 chests of tea into Boston Harbor.

Samuel Adams, who was a professional

agitator, probably did not actually plan or aid the

effort to dump the tea, but he immediately saw the

propaganda value of the protest, and began working to

publicize and defend it this act of political protest.

Adams argued that the Tea Party was not the act of a

crazed mob, but arose out as the only response available

to the colonists who were defending their reasonable

principles and that they took this action as only

remaining option the people had to defend their

constitutional rights.

Governor Thomas Hutchinson had been

urging London to take a hard line with the Sons of

Liberty, as the main protest group involved in the Tea

Party was known.

Back in Britain, even those

politicians and members of Parliament normally friendly

to the plight of the colonies were shocked at this

apparent act of lawlessness they united with the more

conservative elements in Parliament against the colonies.

Prime Minister Lord North declared, "Whatever may be the

consequence, we must risk something; if we do not, all is

over." The British believed that the Tea Party could not

go unpunished and responded by closing the port of Boston

and put in place other laws known as the "Coercive

Acts".

In America, Benjamin Franklin stated

that the destroyed tea must be repaid, to the amount of

£90,000 (English Pounds). Robert Murray, a New York

merchant went to Lord North with three other merchants

and offered to pay for the losses, but the offer was

turned down. A number of colonists were inspired to carry

out similar acts, such as the burning of the Peggy

Stewart. The Boston Tea Party eventually proved to be

one of the major reactions leading up to the American

Revolutionary War, which began in April of

1775.

In February of 1775, Britain passed

the Conciliatory Resolution which ended taxation for any

colony which satisfactorily provided for the imperial

defense and the upkeep of British officers. This act did

not stop the momentum toward war that had been building

for many years.